(Reblogged from http://www.lesliefeinberg.net.)

(Reblogged from http://www.lesliefeinberg.net.)

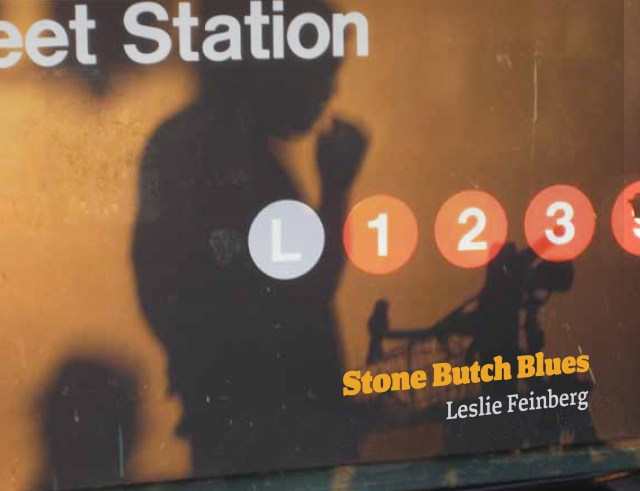

The 20th Anniversary Author’s Edition of Stone Butch Blues is available in multiple formats:Click this link to automatically download your free PDF copy: Stone-Butch-Blues-by-Leslie-Feinberg.pdf (48730 downloads)

Order an at-cost print edition through Lulu.com.

About The New Edition

Leslie Feinberg worked up to a few days before hir death to ready the 20th anniversary Author’s Edition of Stone Butch Blues, to make it available to all, for free. This action was part of hir entire life work as a communist to “change the world” in the struggle for justice and liberation from oppression.

This Author’s Edition of Stone Butch Blues is dedicated to CeCe McDonald, a young Minneapolis (trans)woman of color organizer and activist sent to prison for defending herself against a white neo-Nazi attacker.

“This Is What Solidarity Looks Like” is a slideshow Feinberg developed with the help of scores of activist photographers, in order to document the breadth of the global organizing campaign to free CeCe McDonald.

Stone Butch Blues, Leslie Feinberg’s 1993 first novel, is widely considered in and outside the U.S. to be a groundbreaking work about the complexities of gender. Feinberg was the first theorist to advance a Marxist concept of “transgender liberation.” Sold by the hundreds of thousands of copies and also passed from hand-to-hand inside prisons, Stone Butch Blues has been translated into Chinese, Dutch, German, Italian, Slovenian, Turkish, and Hebrew (with hir earnings from that edition going to ASWAT Palestinian Gay Women). The novel was winner of the 1994 American Library Association Stonewall Book Award and a 1994 Lambda Literary Award.

Feinberg commented on Stone Butch Blues in hir Author’s Note to the 2003 edition:

“Like my own life, this novel defies easy classification. If you found Stone Butch Blues in a bookstore or library, what category was it in? Lesbian fiction? Gender studies? Like the germinal novel The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe/John Hall, this book is a lesbian novel and a transgender novel—making ‘trans’ genre a verb, as well as an adjective…

“People who have lived very different lives have generously related to me the similarities they recognized in these pages with their own struggles—the taste of bile; the inferno of rage—transsexual men and women, heterosexual cross-dressers and bearded females, intersexual and androgynous people, bi-gender and tri-gender individuals, and many other exquisitely defined and expressed identities.”

In hir 2014 Author’s Note to the 20th anniversary Author’s Edition, Feinberg reflects that language usage had changed in naming the sex and gender spectrum zie/she had so eloquently described in 2003:

“The use of the word ‘transgender’ has changed over the two decades since I wrote Stone Butch Blues. Since that time, the term ‘gender’ has increasingly been used to mean the sexes, rather than gender expressions. This novel argues otherwise.

“I have been isolated by illness from discussions about language for more than half a decade.

So I can only note that, like planes, trains and automobiles, the same technological vehicles of hormones and surgeries take people on different journeys in their lives—depending on whether their oppression/s is/are based on sex/es, self/gender expressions, sexualities, nationalities, immigration status, health and/or dis/abilities, and/or economic exploitation of their labor.”

Illness and then hir death in 2014 kept hir from a further task for the Author’s Edition:

“I had hoped to write an introduction to place this novel within its social and historical context, the last half of the 20th century. Context is everything in politics, and Stone Butch Blues is a highly political polemic, rooted in its era, and written by a white communist grass-roots organizer.”

But hir earlier words still resonate with the meaning of Stone Butch Blues for old and new generations of readers:

“[With] this novel I planted a flag: Here I am—does anyone else want to discuss these important issues? I wrote it, not as an expression of individual ‘high’ art, but as a working-class organizer mimeographs a leaflet—a call to action….

“I am typing these words as June 2003 surges with Pride. What year is it now, as you read them? What has been won; what has been lost? I can’t see from here; I can’t predict. But I know this: You are experiencing the impact of what we in the movement take a stand on and fight for today. The present and past are the trajectory of the future. But the arc of history does not bend towards justice automatically—as the great Abolitionist Frederick Douglass observed, without struggle there is no progress….

“That’s what the characters in Stone Butch Blues fought for. The last chapter of this saga of struggle has not yet been written.”

Stone Butch Blues has probably touched your life even if you haven’t read it yet.—Alison Bechdel, creator of Dykes to Watch Out For and Fun HomeStone Butch Blues is a powerful novel written by a founder of the contemporary transgender movement.—Susan Stryker, former executive director, GLBT Historical Society[Feinberg is] a historian, an activist, a relentless bridge-builder. The one whose 1993 novel, Stone Butch Blues, gave the word transgender legs. —Village Voice

Stone Butch Blues is a gift from one of the most inspiring and revolutionary voices of our time.—Emanuel Xavier, author of Americano